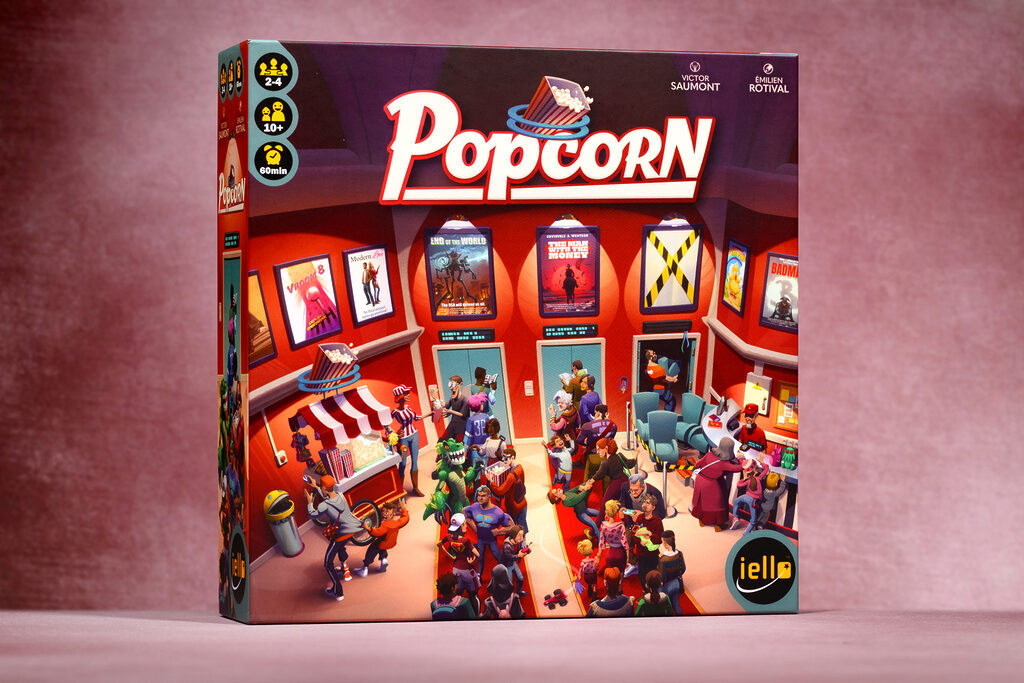

Victor Saumont’s Designer Diary for Popcorn 🍿

Hello! My name is Victor Saumont, and Popcorn is my second published game.

Since I have always enjoyed reading designer diaries, I thought it was my turn to share the creation story of my game, which premiered at the Cannes Festival…for board games — the famous FIJ — in February 2025, seven years after the initial idea.

Discovering Modern Board Games

Although I have been involved in the poker world for ten years, it wasn’t until early 2018 that I discovered modern board games thanks to a game of Codenames.

That game was a huge revelation for the creative person I’ve always been, leading to a new obsession alongside cinema and poker: game design. I started playing as many games as possible, creating my first prototypes (which were often failures), attending board game festivals, and quickly joining a group of French designers (La Ligue Extraordinaire des Auteurs Franciliens, or L.E.A.F.) to test my early creations with other aspiring designers and more experienced ones.

Popcorn: Theme Before Mechanisms

After a few unsuccessful attempts with prototypes — often abandoned after the first crash test — I had the first idea I wanted to pursue further: a board game about cinema.

Cinema was my first passion. At 13, I dreamed of becoming a filmmaker. I made a few short films and documentaries about poker, and wrote some TV series projects, so when I discovered this newfound passion for board games, that was the first theme I wanted to explore.

From the start, my vision was clear: I didn’t want players to create a movie during the game, but rather manage a cinema by choosing the right films to screen for the audience.

The Aging of Films

My primary goal for this project was to stick as closely as possible to the theme. I had often heard that a designer starts a project with either a mechanism, a theme, or a specific component. For Popcorn, it was undoubtedly the theme that came first and drove the research for the game’s mechanisms.

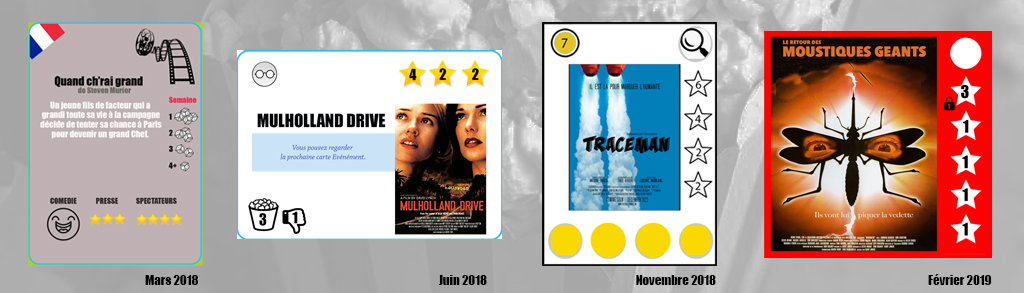

The first idea that excited me, and the only one at the beginning of the process, was the concept of films aging over time. A movie that has been showing for several weeks attracts fewer viewers and generates less revenue each week. In the early drafts of the design, each film granted victory points, which quickly evolved into bags of popcorn, with values decreasing over time. My initial intent was to reward players who knew how to choose the right moment to change their films and optimize their programming.

I researched whether this aging mechanism had been used in recent games and came across Paper Tales by Masato Uesugi (published by Catch Up Games), which reinforced my idea of an evolving tableau. This encouraged players to seize opportunities as they arose, which resonated with my personal gaming style — more tactical than strategic.

Managing the Audience

Another core idea of this project was to simulate the arrival of an audience in cinema halls and create a game about managing spectators (represented by meeples). My initial vision was that the audience would be drawn from a shared bag each week, with numbers fluctuating based on events, e.g., cinema festivals, bad weather, etc.

I worked extensively on this idea with my friend Elie, a filmmaker (and now a César-winning one in France!) who joined the project for a few months. We tested many approaches, but none were successful. The biggest issue was distributing the meeples effectively.

A blockbuster would attract a certain number of meeples of its color, while the other films shared the rest. Even though we liked the idea of winning by selecting “independent films”, we couldn’t find a way to make them appealing enough for players.

One idea we particularly liked was customizing the shared bag with regular clients of our cinema. By adding meeples in our color, we ensured some spectators would come directly to us. It sounded great on paper, but in practice, our loyal customers were too diluted in the bag to make a significant impact. Since everyone contributed meeples, it didn’t create meaningful differences between players.

Bag-Building

As a fan of the bag-building mechanism, especially in Orléans and The Quacks of Quedlinburg, I had wanted to test this mechanism in Popcorn for months. Instead of a shared bag, what if players managed their own audience?

Each week (i.e., each round), players would draw a certain number of spectators who had decided to visit their cinema. The challenge would then be to offer films that appealed to them — or, at least, to make the best use of the meeples drawn to earn more popcorn.

The good news was that we could imagine the cinema’s audience growing over time, creating a sense of progression. This led to the idea of an attendance track, which determined how many spectators visited each cinema each week. Players would try to climb this track to attract more and more visitors.

The “Eureka” Moment

Now that we had meeples to manage, what should players do with them? It’s hard to count how many months it took to find the breakthrough idea, but I went through many unsatisfactory iterations before reaching the solution.

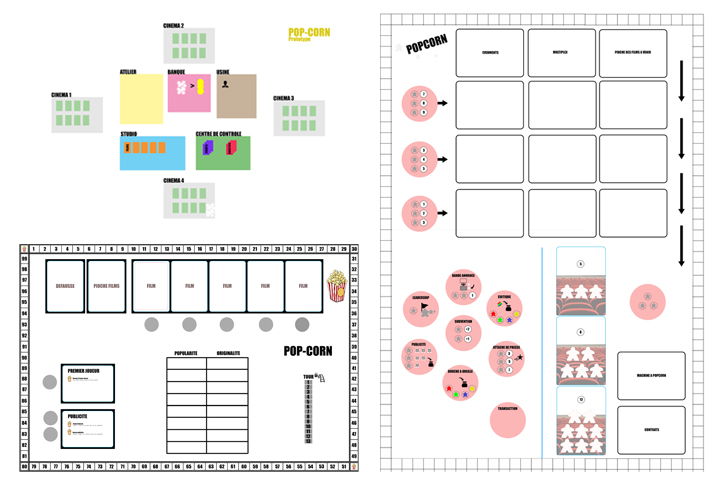

The first idea was a worker-placement system: Players would draw meeples and place them on actions available to everyone. After one or two tests, I abandoned it. Not only did it feel thematically off to send spectators onto a central board, but my fellow designers quickly shut it down: “This isn’t original — it’s just classic worker placement. You need something better!”

Another option I considered was a system similar to Orléans, with a personal board featuring actions like earning money, buying films, increasing attendance, building theaters, and earning popcorn. This worked better, but everyone ended up wanting to do the same things to grow their cinema. Worse, selecting the right films had almost no impact in this version. Frustrated, I put Popcorn on hold and focused on other prototypes, waiting for inspiration.

Months passed without a breakthrough. The prototype sat in a box on top of my wardrobe. Though I often thought about it, I had largely given up…until the moment of revelation.

One evening, while going to the movies, I looked at the film posters and had an epiphany: The key game actions could be tied to the movies themselves. What if I merged the film-aging concept with the actions players needed to take?

The idea was simple: All available game actions would be provided by the movie cards. The thematic concept was that each film would generate different benefits — some would sell more popcorn, others would generate more money (e.g., 3D films), and some would have strong word-of-mouth, attracting new spectators.

Mechanically, the actions players wanted to take would be tied to the films, with four actions available in the first week, three in the second week, and so on.

I remember that this “Eureka moment” unlocked a lot of things. It was also at this moment that I started thinking about the direction to give to the films. The yellow ones would be comedies that increase attendance, the red ones would be action films that bring in popcorn sales, the blue ones would be dramas that allow for contract negotiations, and the green ones would be fantasy films that help build better theaters.

As a side note, we were in the middle of the Covid lockdown, and I needed to imagine a world where we could once again go to the movies…

Filling the Theaters

From the first iterations of the game, I was obsessed with the idea of a full theater. For me, it was the key to unlocking a major bonus. If you fill your theater, you earn a reward depending on the size of the room. The only problem was that if you drew four meeples on your turn and used them to fill a four-seat theater (simulating a 400-person room) to earn, say, 5 popcorn, you hadn’t really done much during your turn.

The idea was that every spectator should serve a purpose while still maintaining the notion of a full theater. The solution emerged during a playtest night with my author group (them again!), when one of them suggested that a meeple of the film’s color could trigger one of the available actions. This way, thanks to the right meeple you would gain both an action and a reward for filling a theater.

A few days before the Cannes Games Festival in 2022, I had a small revelation after yet another test session, one in which I felt for the first time that the game was actually working. I found a way to make premiering a film valuable (by earning a spectator of the film’s color) and, most importantly, improved the theater-building system.

One key element that unlocked a lot of things was the concept of choosing theaters. Choosing to fill a small theater for a bonus or, conversely, opting for a larger one to benefit from a specific Film card effect introduced a simple yet interesting dilemma. The size of the theaters also had an impact on film choices.

After playtesting this version, I decided to pack the prototype in my suitcase with the plan to play a few games during the Off sessions. I brought four or five games that I had scheduled meetings with publishers for, but Popcorn was not the one I intended to showcase — it was a project taking shape but far from finished.

Off the Record

Encouraged by the tests at the Off, where the first full games were played (even though I still didn’t have an endgame condition), I started mentioning Popcorn at the end of my author meetings when I felt an editor might be receptive to this kind of thematic proposal: “I also have this, a game about cinema in which you draw meeples and place them on films you’re screening to earn popcorn.”

The idea intrigued some editors, who asked for a print-and-play or the rulebook. The originality of the theme stood out, and I was thrilled.

Then came the lightning strike from Florent, a project manager at IELLO. The pitch resonated with him, and the game seemed to check all the boxes of what he liked. He asked me to send a prototype. I was ecstatic, even though nothing was guaranteed yet. IELLO is a company I respect. It publishes relatively few French-designed games compared to the number of localizations they do through KOSMOS, Devir, and CGE, but IELLO is also the publisher of Codenames, and that game was my gateway into modern board games four years earlier.

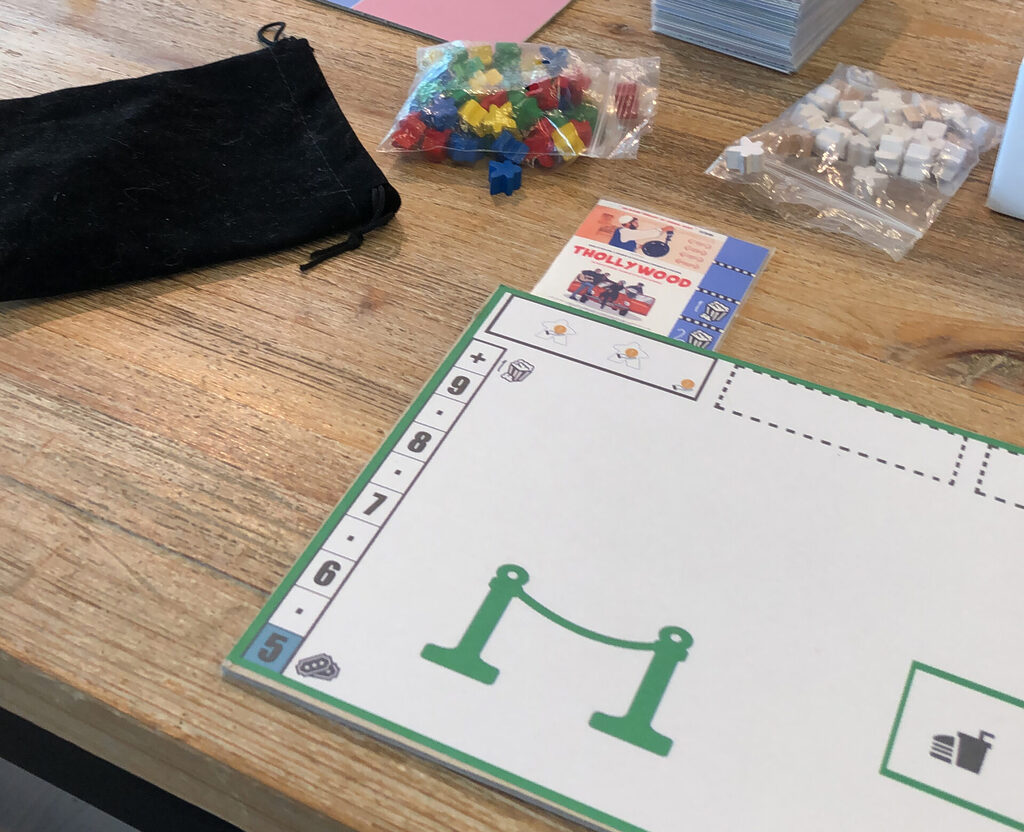

I still had a few adjustments to make before sending the prototype, especially incorporating ideas from the ten or so tests during the Off. I also had to write the rulebook, which I hadn’t even considered until then.

The IELLO Deal

A few weeks later, I sent Florent my best-looking prototype, complete with handmade bags made by my wife, a few rule adjustments, and the secret hope that they would like the game beyond just the pitch.

Two weeks later, I received a magical email: Florent announced that they were signing the game. Oh, my god! It’s hard to describe the emotions that followed. Surprise, first of all — everything happened so quickly when just six months earlier, I had nearly abandoned the project because it was stalling. Above all, immense joy in seeing this project, so close to my heart, signed by a company I greatly admire. I was aware of my luck, the alignment of the stars, and the decisive meeting with Florent on a beautiful February afternoon at FIJ.

The Beginning of Development

Once the contract details were sorted out, development officially began in July 2022. I was well aware that the game was far from finished. The first encouraging iterations dated back to FIJ, but there was still a lot to do to refine it.

I was a little apprehensive since this was my first time collaborating with a publisher along these lines. The development of Diferencio, my previous game at KYF Edition, had been almost entirely hands-off for the designers because the game was primarily driven by visuals — but with Popcorn, mechanical aspects needed to be improved, in addition to the illustration work that had to be done.

A Handful of Meeples

Early on, I faced an unexpected request from my project manager that I hadn’t anticipated: material constraints.

Publishers have production concerns that designers often don’t realize, and a game with 130 meeples (as in my prototype) was too costly to produce. My project manager ran some estimates and concluded that the number of meeples had to be reduced, especially since their internal playtests always ended with plenty of unused meeples.

To address this, I came up with a simple yet game-changing idea: Each player would start with nine meeples, five white (neutral spectators) and four colored (with film preferences). Initially, players could gain new white and colored meeples through the “word of mouth” action. Later, we removed the ability to gain white meeples entirely. Instead, when the reserve was empty, performing the action would allow players to take a spectator from an opponent’s exit zone.

This thematic tweak fit well, the idea being that your movie could attract people who would have otherwise gone to another cinema.

Player Interaction

This adjustment not only reduced the number of meeples needed, but also introduced more player interaction — without being too harsh. It was well received by my project manager during IELLO’s internal playtests. We even later decided to further limit the reserve, so that spectator “stealing” would happen earlier in the game rather than just at the end.

Originally, interaction was also represented by black meeples, which we later removed. Not only did they pose thematic issues, but they were also too punishing. Players could place black meeples into opponents’ bags, and once drawn, they would be deadweight for the rest of the game. If multiple players ganged up on someone, it could ruin their experience.

Instead, we replaced this with sending white meeples to opponents. White meeples weren’t as problematic since they could still help fill theaters and trigger film card actions. Players also had ways to get rid of them through certain actions.

Balancing the Films

One of the most challenging aspects of development was balancing the film cards. Since the prototype’s earliest versions, my author friends had warned me: “Your game is going to be a nightmare to balance!”

They were right. Some actions could be repeated multiple times if players placed multiple meeples of the right color in a theater. We solved this by placing the most powerful actions lower on the cards, limiting their availability.

It took many tests to evaluate the power of each action and compile everything into a massive Excel table, factoring in the action’s position on the card and its impact.

Simultaneous Play

The major part of the development, and the reason for the delay that prevented the game from being presented at the Sabliers d’Or in France, was IELLO’s desire to make the game playable simultaneously. After the Ancient Knowledge precedent, in which some players complained about the long wait between turns with four players, they worried that turns in Popcorn could also be lengthy. Players would take time to place their meeples in the rooms and complete their actions.

The solution was simple, but not without challenges: make simultaneous play possible. Players receive their new spectators for the week and perform their actions simultaneously, as if they were managing their cinema individually. The main issue with this was managing actions that required a specific turn order, like building new rooms or word-of-mouth actions.

This simultaneous play choice significantly reduced the game time (almost by half). Since building rooms was problematic (both thematically and in terms of timing), we moved this action between turns and removed it from the film cards. As for the word-of-mouth action, it required adding an additional board — the advertising board — to signal that a player would acquire new meeples in the upcoming week.

Building Rooms

Room construction was a key element of the game and a major challenge during development. Notably, there was the introduction of colored seats with IELLO and the idea of starting the game with an unbuilt room. The cost of rooms, the available powers on the seats, and fine-tuning the fact that a filled room triggers an action from the film cards were all repeatedly tested to ensure each room was appealing.

The decision to remove the construction action from the film cards also greatly simplified the timing of the building process — a frequent source of frustration for players during their first playthroughs.

Creating Films

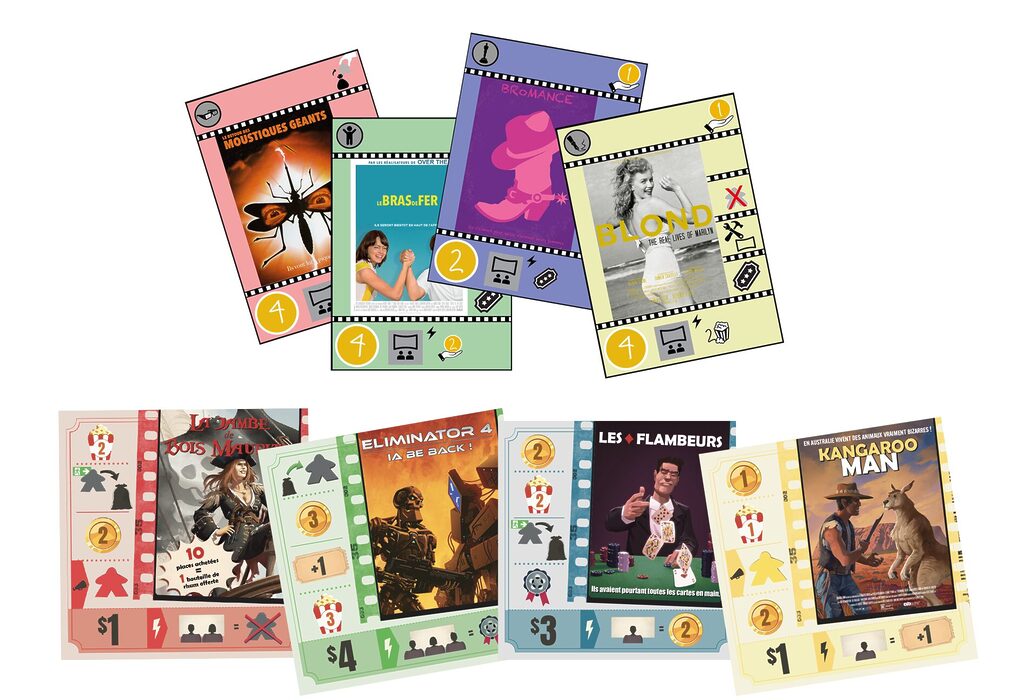

As for the graphic design and illustrations, I’ll let illustrator Emilien Rotival describe the various stages of creating the cover, the films, and the game elements — but let me first share a little about the creation of the films themselves.

Starting in 2019, I used the long moments of doubt about the game’s mechanisms to create fake films that would feed into the theme. The technique was simple: I took existing movie posters and reworked them by changing the title (and sometimes the tagline) and adding Easter eggs for fun. While this was quite time-consuming and unnecessary at the prototype stage, it was enjoyable, and I think this work helped attract attention to the game — particularly at the Cannes Off.

Once the game was signed, I eagerly anticipated inventing the films that players could choose to showcase. My project manager and I spent a lot of time discussing what type of films to create. We were not allowed to use existing films, and we didn’t really want to parody them as in Reiner Knizia‘s Dream Factory. As a film lover, I had hoped to slip in references to some of my favorite films, often obscure ones. However, IELLO’s distribution ambitions meant we had to focus on references that would resonate with a broader audience.

The idea, therefore, was to focus on film genres rather than specific films: rom-coms, horror films, pirate movies… It’s up to the players to find connections to existing films — and there are quite a few! In total, we came up with 48 films in four genres: comedy, drama, action, and fantasy/horror. My project manager also had a lot of fun coming up with a few playful titles.

Premiere at Cannes – Coming soon in English!

In the end, three years passed between signing the game and its arrival in stores. Little by little, I delighted in discovering the visuals created for the game — the cover, boards, films — and thought to myself that I was living a dream. Popcorn was finally going to be released!

After a preview presentation at Cannes during the International Games Festival — and what better place for a game about cinema? — the game will be available in French starting March 12 and in English in the second half of 2025. I hope you will enjoy playing it as much as I enjoyed every step of its development.